“Be strong, be strong, and let us strengthen one another,” proclaims the ancient refrain; but is there such a thing as too much strength?

When we speak of weight training as part of the athlete’s life routine, it is well-established through countless observations and studies that those who are stronger in complex resistance exercises possess greater athletic potential (assuming they choose to embark on the long journey that actualizes that potential).

This immediately raises the obvious questions; how do we know when strength is the limiting factor in athletic development? And when will adding more strength fail to yield additional athleticism, if at all?

In this post, we will attempt to bring some order to the uncertainty that afflicts many ball sport players in their strength training routines, and briefly review the following topics:

- What is strength and what is power?

- Pure strength versus utilizing strength in space.

- The relationship between strength and the chosen sport.

- The resources required for strength development within a training program.

- Muscular activation and control versus pure strength.

- The relationship between muscle mass and strength.

- The best way to use the weight room for athletic purposes for a healthy athlete?

- Additional legitimate uses of the weight room; beyond maximal strength.

What Is Strength and What Is Power?

Maximal strength, in the context of this article, is a specific capacity of the nervous system concerning the recruitment of as many motor units as possible in response to large external resistance challenges.

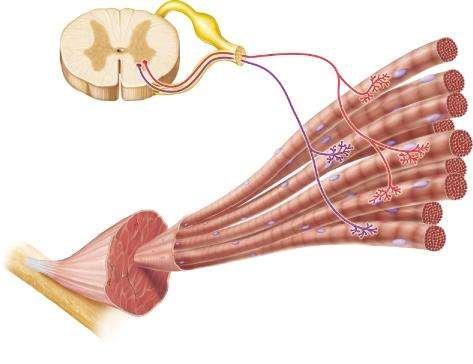

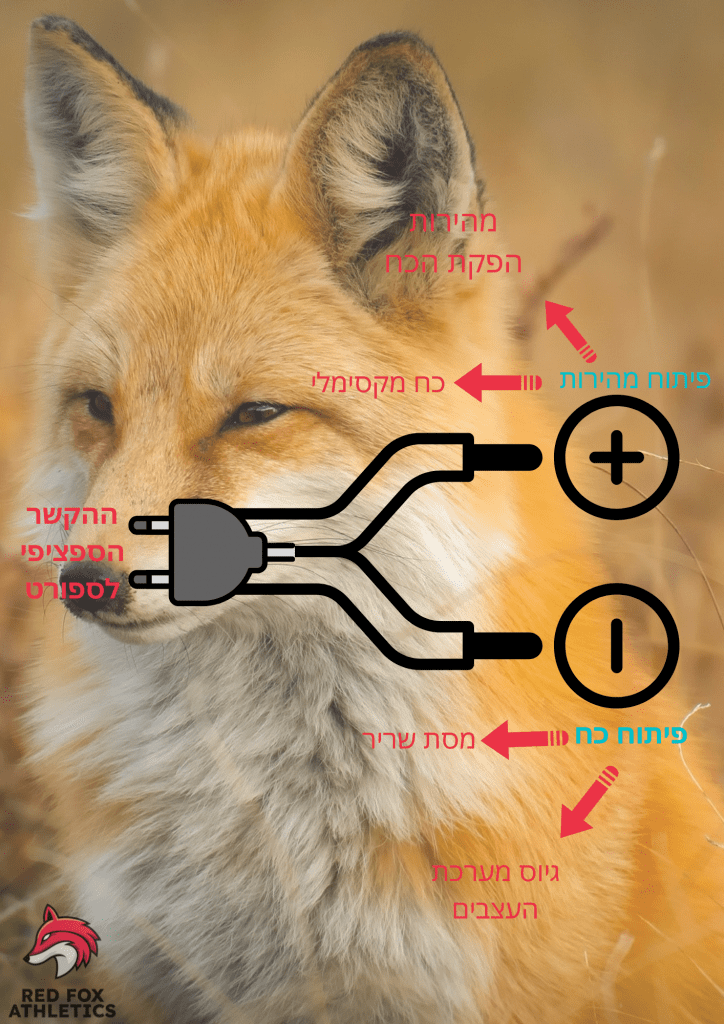

The motor unit in question is a mechanism composed of a small conducting branch of the nervous system that connects to muscle fibers (the motor neuron) through “splitters,” as can be seen in the image.

We can describe the motor neuron as the main electrical supply in a house sending current to all outlets, while the muscle fibers constitute the electrical appliances connected to those outlets.

A single motor unit, if we describe it in electrical terms, would be the wire running from the switch in the breaker panel to the wall outlet, including the specific device plugged into that outlet.

Muscle fiber strength can be measured scientifically with sensors; however, in the training world, given adequate technique and sufficient training, it can also be effectively measured through barbell lifts, throws, and similar standardized strength exercises. One can reasonably assume that someone who lifts 140 kg in the squat is stronger at the muscle fiber level than someone who lifts 60 kg in the squat; again, given similar body fat percentage, body weight, and technique between the two.

To visualize maximal strength in another way, we can describe a household outlet to which two cell phone chargers are connected; one an expensive fast charger, and the other a cheap charger from AliExpress.

The more expensive charger will draw more current from the wall (utilizing more of the main electrical wire) and charge the phone faster. The cheap charger cannot draw much current from the wall because it simply is not built for it (it lacks heat sinks, lacks sufficient conductors, etc.) and will therefore charge the phone slowly. This is precisely the description of maximal strength in the human body; the ability to draw more current from the nervous system and recruit more motor units for the task.

Pure Strength Versus Utilizing Strength in Space

When discussing pure strength, we typically do not add the element of time to the description. We assume there is unlimited time to produce all that strength, such as in a deadlift or squat; the repetition will be completed whenever it is completed, as long as it is completed. The judge does not measure how long it took to lift it.

However, in most Olympic disciplines, especially in track and field events and ball sports, the nature of competition exists within certain time constraints. The running stride must be faster than the competitor’s, the ground contact time must be lower than the competitor’s, the jump must come quickly; otherwise, the competitor will reach the ring, ball, or net first. Thus, we need to separate right now the maximal capacity (maximal strength without time constraints) from the specific capacity (strength under time constraints).

We will use two key terms to describe the use of strength for specific sport performance:

- Rate of Force Development

In neuromechanics, the rate of force development is the time it takes for a motor unit to reach its maximal utilization from the moment of command. We can imagine the bottom of a heavy squat; an athlete who has worked on their neural and technical capacity to reach maximum force very early at the bottom of the squat will likely defeat an athlete who always “took their time” during squat repetitions. Athletes generally want a very fast rate of force development because they want to utilize their strength early in movements to win battles before their competitor does.

In barbell lifting specifically, producing maximal force very early in the movement will lead to higher momentum, which will reduce the chance of getting stuck mid-repetition in weaker leverage zones.

- Total Power Output

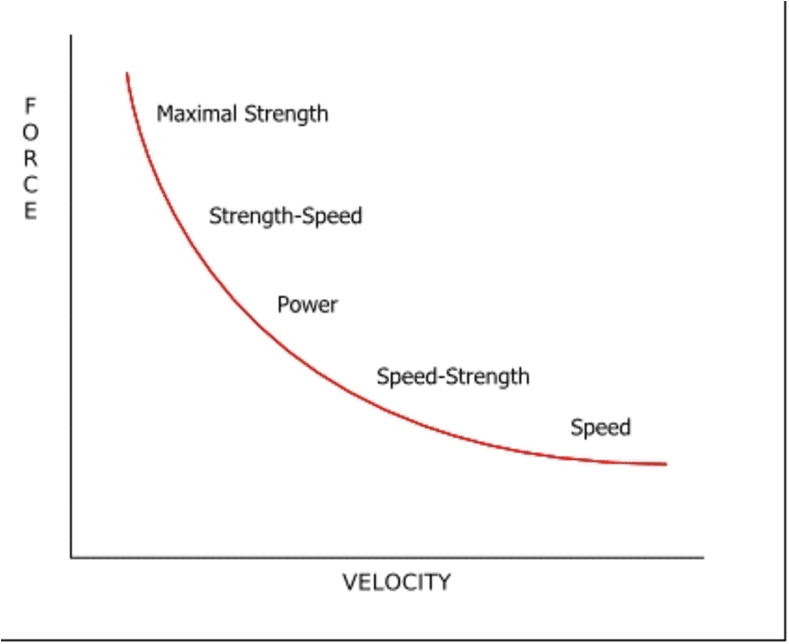

The description of total power output (Force × Velocity) is called “P” in physics and denotes the value “Power”; this term will be closer to describing athletic performance than describing force alone or rate of force development alone.

If rate of force development asks the question “how quickly did you reach maximal contraction”; then power asks the question “what did you actually do with that speed.”

For example, in the squat, the lower the weight, the higher the rate of force development we can achieve, but since there is no weight on the bar, we did not “do” much with it, or in scientific terms, the “power-P” will be low.

Power in our context is described by the equation “Force × Velocity” or in barbell slang; “how much weight you put on the squat × how fast you did the rep.” Meaning, as velocity increases, weight decreases and power remains low. As weight increases, velocity decreases and power also drops. Notice this trick? This is where training science begins to get complicated and develop different approaches to address this paradox.

The reason for this is that for a motor unit to reach its maximal utilization, it needs sufficient external resistance (it is biomechanically impossible to produce maximal force on a bodyweight squat because the sensors on the muscle fibers will sense no mechanical threat or challenge and will not activate the units aggressively).

These three together: maximal strength without time limits, rate of force development under time constraints, and total power output (which is a combination of the previous two) paint the skeleton called the art of training programming; and because each affects the other, hundreds of annual training methodologies have developed to address this matter from various angles.

Some believe that each factor should be separated and worked on individually; because they believe there are not enough resources available in the body to work on everything without falling into overtraining.

Some advocate combining all factors in the same workout (the conjugate philosophy common in certain circles, CrossFit, etc.).

Some prefer to include all these elements within a training week or month but not necessarily in the same workout; while playing with the volumes of each component throughout the year (this is the Fox’s approach; for it is the only one that merges human psychological factors into the training process while remaining scientifically sound).

This is also the approach of many of my teachers, each in their own discipline. Louie Simmons z”l; a Western pioneer in the practice of strength training for professionals; called this method “the Conjugate System” and taught it until his passing in April 2022.

The Relationship Between Strength and the Chosen Sport

As we see, strength in itself is very important for track and field and ball sport athletes; but only when combined with the other factors in the equation (rate of force production + power). So what is the relationship between the sport itself and the chosen resistance program?

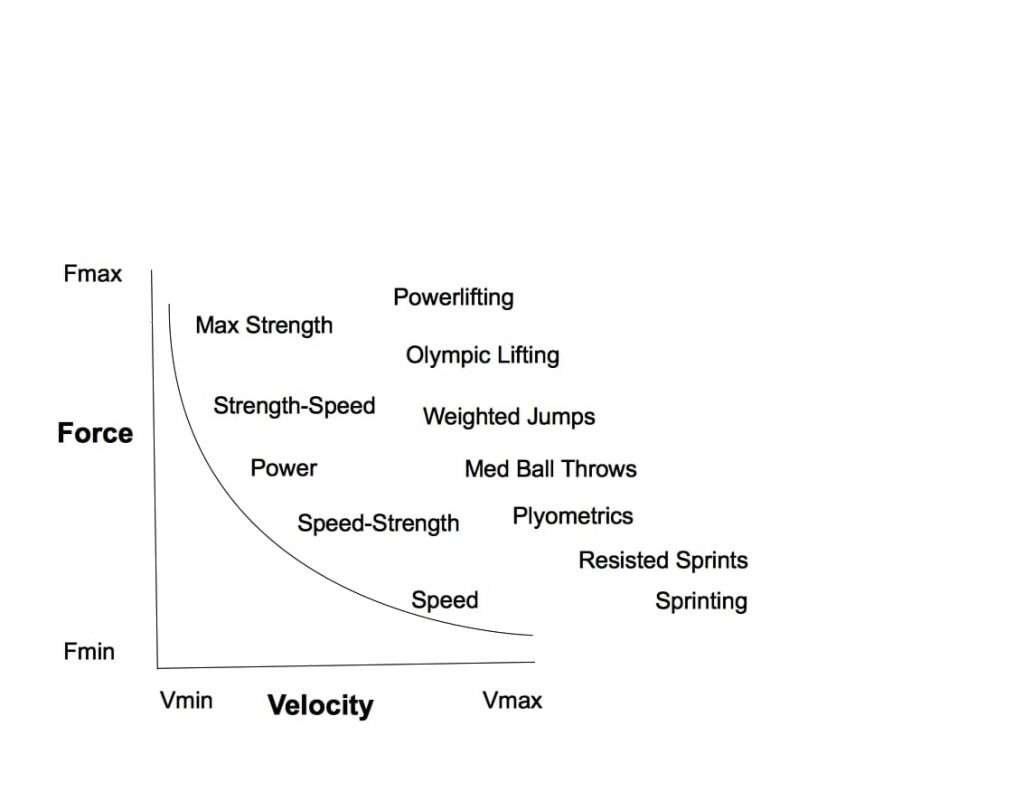

In the graph below, we can see where certain actions fall on the velocity/force relationship graph. Before we can plan an appropriate annual program, we need to ask where the sport “feels at home” on the graph.

We can see that powerlifting, which consists of a maximal competition of squat, deadlift, and bench press, falls high in force demands and low in velocity demands. Does this mean a powerlifter does not need to train speed? Not at all; it simply means that effective speed for a powerlifter will be one or two levels south on the graph from the competitive demand, meaning fast squats at about 40 percent of max, power cleans, and so forth. Sprints or throws of various kinds will not be particularly beneficial from a multi-year perspective and therefore emphasis will not be placed on very fast actions with light implements.

Soccer and basketball span the middle zone of the graph to the extreme end of velocity, meaning there is a combination of very fast movements to plyometric movements with bodyweight (middle of the graph); such a sport will benefit from both extreme ends from a multi-year training perspective, but because of the demands of the sport itself regarding specific technical training, we typically cannot find resources to train barbells at 90-100 percent intensity.

We need to analyze what actually happens in the sport training itself to know what to plan in a multi-year program.

If a significant portion of an average basketball team practice contains about 50 maximal plyometric contacts (rebounds, blocking jumps, maximal sprints, etc.); we can assume that the nervous system will be well-practiced at these volumes, which will make external conditioning training using the same elements and same execution manner physiologically redundant and entirely inefficient.

External training for the sport but in its service; will need to innovate either in a “fresh” zone on the graph, or in practicing a different manner from what naturally occurs in training itself.

This is a good argument against the “sport-specific training” myth common in certain circles, held by those who believe the only valid training for an athlete is training that completely mimics what is done in practice, all year long, until retirement. (For example, a volleyball player who only practices spiking approaches or a tennis player who practices serving with a 5 kg racket.)

The purely specific approach goes against neurophysiological science and against every known mechanism of physiological improvement through training. It is equivalent to a chef whose food is very salty, so he adds more salt, expecting to be told his food is not salty. After all, it is well known that mere multi-year participation in the sport itself does not necessarily lead to elite athletic performance; so why would more of the same medicine, without any improvement, upgrade, or change, do the job?

Standing against the outdated specific approach is the muscular approach, discussed in the article “Approaches to Capacity Development” on this site.

The common muscular approach assumes that since all human action originates in muscle contractions; resistance training at various contraction levels (slow, fast, isometric, etc.) will produce results in sport.

This approach too is far from the truth, since muscle is not the source of all movement in humans, but rather psycho-motor processes that begin in the nervous system and are interwoven with the player’s individual psychology. Only afterward do we arrive at the engines (muscles); which derive their mode of action from primitive and less-researched nervous and cognitive systems (because they are far more complex).

For the car enthusiasts among us; we can describe the muscular system with all its qualities and contraction types as the engine in a car. The fact that a car has a 3.5-liter engine does not mean it will be faster or more agile than a car with a 2.5-liter engine, because there are other components such as power-to-weight ratios, engine management computer, air and fuel injection, and so forth. One can certainly find cars with smaller engines that, thanks to better ECU tuning, addition of a turbo, etc., will defeat cars with larger engines.

For us to be responsible in planning external training for ball sport athletes, we will need to take these factors into account as well; even if fiddling with them is less pleasant and easy than nice, sporty barbell training.

The Correct View of Force/Velocity Relationships for Ball Sport Athletes

So we have already deduced that maximal strength in the weight room is very important, but excessive focus on it during a training year will not lead to extraordinary results.

We have also deduced that speed with all its components is very important, but without sufficient strength in the weight room, it too will be limited quickly even if trained perfectly. Performances of explosive acceleration from a standing position, for example, are very dependent on the athlete’s relative strength (how much you weigh × how strong you are) and will favor stronger athletes.

The correct way to view the relationship between speed and strength in sport is one that recognizes the neurological basis of movement (the nervous system, psychological state) at the top of the pyramid of importance.

True speed and movement matters, meaning the business of making a person faster and more athletic in space, are distinctly unnatural to human biomechanics, which tends toward endurance anyway. If so, most of the hard work will be in new motor learning that draws from the animal world of quadrupeds and channels it to bipedal humans, both biomechanically and psychologically.

This is something that will need to be done on a weekly basis, throughout the entire training year, with the understanding that due to the unnaturalness of speed in human evolution, ceasing this emphasis will lead to an almost immediate decline in sharpness and results.

Once there is a motor/psychological skeleton running annually and providing the unceasing motor learning, one can treat the more classic training of strength and classic speed (running, jumping, agility, etc.) the way we treat engine displacement and horsepower in cars. Improvements in maximal strength will constitute engine displacement improvements, while speed improvements will constitute horsepower improvements. The annual program (and annual efficiency) will be a sophisticated dance between the two, based on (in descending order of importance) resources available from main training, specific weaknesses and strengths of that individual, access to facilities and coaches, and financial ability to hire experienced professionals.

The Resources Required for Strength Development Within a Training Program

In the art of annual training programming, there is near-universal consensus: once two fitness components compete for the same “zone” in the nervous system or muscular system, they will rival each other instead of improving.

Let us divide common athlete activities by their intensity on the nervous system in descending order:

- Full sport training by the head coach, sprints above 90 percent, maximal jumps, maximal medicine ball throws, barbells above 80 percent of maximum, maximal agility, explosive weightlifting, non-maximal training to failure in the weight room.

- Long runs over 100 meters at 80 percent speed (very common in the soccer world), barbell training in the 8-12 rep range, isometric barbell training.

- Easy continuous running, barbell training above 12 reps, physiotherapeutic barbell training (concerning posture, movement quality, etc.), and various warm-ups.

Now here is the trick: there is no specific problem with combining components from the same category in the same workout or day; the problem is when we interfere with the recovery process (where improvement actually occurs) with more training from the same category. For example, if on Sunday we did maximal squat sets with 6 reps plus athletics training, then on Monday it would be highly advisable not to load the intense category, and aim for the other two categories such as upper body repetition training, continuous running, etc.

There is one caveat to this and that is work volumes. If we did not reach fatigue in that specific category on that day for some reason, for example a beginner athlete who cannot perform exercises maximally at all and affect the nervous system (because they can only recruit 30% of it anyway if they tried, due to their inefficiency); that athlete does not meet the physiological laws above at all and can train even every day.

Conversely, if the athlete is very advanced and uses the full neural potential for movement, even a single fast sprint set can stop an entire workout and send them home for the rest of the week.

In the Fox system, we have a rule that if an advanced and experienced athlete sets a personal record in a neural component like sprint or jump, they finish the workout and go home with a meal courtesy of the coach. The underlying assumption is that if the nervous system expressed itself in such a way that they broke a personal record, then any additional stimulus to it for that day will constitute overtraining. Since this happens only once every few months at most among very experienced athletes, this is a rule we are willing to keep.

In summary, speed components and strength components compete for the same resources in the body (both drink the same fuel), and they must be used wisely both during the training week and during the training year composed of season, pre-season, and off-season.

Muscular Activation and Control Versus Pure Strength

When we enter the weight rooms of professional teams across the United States and Europe, we can identify three types of training (or more accurately, three types of coaches).

- Training that emphasizes muscular control, single-leg exercises, slow and controlled contractions with light weight, various isometric contractions, great emphasis on control in the static range of motion and adding difficulty to basic exercises through unstable surfaces or intentionally placing biomechanical weaknesses.

- Various movement training that places emphasis on static movement and breathing exercises on a yoga mat or treatment table, and placing very specific biomechanical difficulties under bodyweight.

- Traditional strength training of 3-6 reps in complex exercises, Olympic lifts, classic hypertrophy training, explosive weightlifting.

We can say that methods 1+2 deal with the quality of muscular contraction as a supreme value (without accounting for the speed or intensity of the contraction), while method 3 deals with the intensity and speed of muscular contraction. Or in other words, methods 1+2 have a holistic physiotherapeutic flavor and method 3 has a “blunt” flavor.

Proponents of methods 1 and 2 will argue that muscular control and strict technique is what will bring results because it is claimed that the muscle is responsible for the contraction on the field and any isolated work on that muscle will lead to transfer of results to the grass.

Proponents of method 3 will argue that physics is physics, and that the force of gravity pushing us forcefully toward the ground is not interested only in our control and isometric contraction quality but mainly in pure force that can resist it.

All these methods are wonderful in themselves and students of each will gain superpowers specific to that method. However, allow me to sharpen several points that bring order to when to use each method:

- When seeking speed and agility in an average player, the muscular control philosophy should come from the athletic direction, not from the weight room; for the simple reason that motor learning is a very specific thing. The proof is that guitar players cannot necessarily play piano despite the fine motor demands from finger muscles being very similar. With this knowledge, we can assume that motor control acquired in the weight room will probably not transfer to the walls of the playing field.

- If we analyze players returning from injuries who have received clearance from the physiotherapist to be handed over to coaches, we will likely see them in the weight rooms focusing on “safe” exercises that are supposed to restore muscular control to the injured area while totally ignoring the fine and powerful motor capacity to which they are supposed to return very soon. This only entrenches psycho-physiological fear in the athlete so that even when they return, they are no longer the same player because they did not restore confidence in powerful movement on the field. Here too, the first approach is destructive.

- Joint mobility and functional breathing training in the style of FRC/PRI; as a primary system for athletic performance, is a bad idea that has never produced elite performance outside the yoga mat. One can draw from them and deposit into athletic training, and one can use them as part of the professional physiotherapist’s toolbox; but from there to a sophisticated capacity development training system, the road is very long.

- Traditional training (method 3) works well for athletes but comes with the risk of poor resource management and increased danger for those returning from injuries; use professionals to assist you in the process! An additional problem with method 3 that the Fox sees constantly is falling in love with the comfortable improvement in classic training; it is so fun to see the weights go up every week that many athletes tend to forget the secondary nature of barbells within a player’s training year.

In summary, control and movement quality are indeed important things, but within an athletic context and not just on yoga mats. Remember the example of learning a musical instrument. If the exercises come to supplement a more comprehensive athletic program, excellent. But when they come stripped of athletic context, the nervous system does not know what to do with this information of the ability to contract the core very slowly, or to breathe into the diaphragm with eyes closed while performing a Bulgarian lunge with six kilograms and lateral band resistance.

The Relationship Between Muscle Mass and Strength

Within the traditional method of strength development, every decent coach and scientist knows that muscle mass is an inseparable part of the potential for strength development. Many times the question “how big is big enough” for a ball sport athlete is asked, and in truth, this is not the right question to ask. What we need to ask is what is the lowest body fat percentage we can be at while still being energetic enough to perform good team practices and quality strength training with weights well above our body weight.

This question already blocks the exaggerated diets of bodybuilders that do not allow them to be alert enough to drive, and also blocks the “bulking” periods where bodybuilders eat massive amounts of carbohydrates to inflate; because body weight that does not translate to improvements in maximal strength in complex exercises is dead weight and therefore inefficient for the athlete.

Indeed, we should not fear the natural addition to muscle mass within a proper training process for a ball sport athlete. As long as the athlete remains at 10% body fat or less, and their additional weight disproportionately increases (for example, 10 kg increase in squat for every kilogram of body weight) their strength in exercises like squat and deadlift, it is desirable and blessed.

Fear not; no athlete in a daily training routine of their sport with limited resources for mass and strength development will be “too big” for the sport. Even when making it an emphasis, retiring from the sport and going all-in on the weights, it is still very difficult to add lean mass.

Stronger and Faster; Good for Fuel Efficiency?

A very interesting effect discussed regularly at the Fox is the ability of maximal speed and maximal strength improvement to indirectly improve speed endurance in ball games.

The question always asked is: “Fox, after all, in a game I will not reach that speed most of the time, so why invest time in it at all instead of training at lower speed and doing more repetitions?”

The answer to this is quite logical. If we return to the car world, and say that a car has the option to reach 350 km/h if it presses the gas, we can only describe with what ease it will cruise at 80 km/h on the highway.

Conversely, if we take an old car with a 1.2 engine, whose maximum speed is 120 km/h and makes a terrible vacuum cleaner noise from the engine on inclines, it will obviously struggle even cruising at 80 km/h, burn a lot of fuel, and experience considerable wear.

From this we learn that improvements to maximum speed will lead to such deep physical and technical understandings that will allow the lower game speeds (by nature) to constitute a smaller percentage of your capacity, or in other words; your “half effort” is going to be your competitor’s sprint; a superpower by any measure.

Of course, specific speed endurance training is still very important. These are the workouts that try to develop the athlete’s ability to be fast and athletic even under lactic acid and fatigue. But since endurance is not the subject of this article, we will suffice with this slight caveat.

Additionally, from a technique standpoint, self-confidence rises when the legs win battles with relatively easy running; something that causes technique to be expressed with greater psychological confidence. This is not only efficient tactically but also minimizes the chance of injury, since the environmental awareness of a person running at a lower percentage of their maximum is better; and they can run and jump with grace and not in “constant war.”

Practical Summary

If you managed to survive this level of theory until now, I will treat you to practical things that you can clip, save, and implement.

- A mature ball sport athlete needs to maintain a deadlift and squat of at least 1.5 times their body weight in order not to be significantly limited in specific athletic training.

- An athlete should aspire, with their coach’s help, to improve their strength to 2 times their body weight and up to 3x and above for non-ball athletes like sprinters and jumpers.

- An athlete should use the weight room mostly in a traditional manner (improving strength and muscle mass) and not in a holistic manner, unless there are physiotherapist restrictions, as they are the supreme authority on health matters.

- The holistic form of muscular control, breathing, and movement in the weight room is not bad or shameful when performed in moderation and with a clear and specific purpose, but when it becomes the emphasis, it loses its contribution to the goal.

- Train all relevant fitness components, all year. A capacity that does not receive continuous work at some volume will fade. If you are worried about overtraining; use a professional coach to plan it correctly.

- The athletic foundation is the skeleton upon which all other athletic improvements rest. From there will come better barbell training, better endurance training, and more efficient technical training.

- An athlete should measure, if it is a ball sport requiring running speed, jumping, and agility, at 10 percent body fat or less to be considered worthy in terms of power-to-weight ratio.

- Remember; at the top of the priority order of the approach to athletic development is the psychological state and the approach to this thing called human speed. After that, the expression of this in the nervous system, and only then the systems operating in the muscles. This is true not only for training but also for decision-making matters. Before buying a house or car, one must understand why it is truly needed (psychology), then tune the bank or financial resources so it does not get upset (nervous system), and only finally pay (muscles).

- As a healthy athlete trained in the weight room, even when heavy, get used to producing force early in the movement and not waiting for sticking points. Break through difficult angles with athletic decisiveness rather than geriatric caution.

- Speed development and strength development are like the plus and minus of a battery; both are necessary and serve the same purpose. What that battery powers (the specific context of the sport) will determine the nature of the training, the proper technique, the proper execution manner, and the mental approach. Annual planning without constant calculation of this important triangle (speed, strength, sport context) will never be complete.

As always, I would be happy to be at your service for any questions in the contact section, the Fox forum, and Telegram. If you have additional ideas or reservations, I would love comments on this article and we can discuss them!

And of course, do not forget to subscribe at the bottom of the site for new article notifications.