Just as a vivid example captures the heart of a learner more readily than abstract rumor, so too does reality television prove more popular with the general public than literary fiction. It is simply easier for the natural human being, operating under the laws of nature, to approach a reality show than a novel.

Yet an equally valid argument holds that fictional literature is actually more real than the immediate gratification of the optic nerve’s dopamine-driven mechanism, which caters to base desires. How can this be?

In fiction, one often encounters authentic human depths that the writer has distilled into a potent essence of universal truth — even though the characters do not exist in reality and cannot be perceived through the eye. This essence employs fiction as a vehicle to convey relevant truth; just as imagination precedes action, though it remains imagination. Thus, fiction serves as an elevated decoding mechanism for the raw, meaningless electrical signals flowing from lens to optic nerve to brain.

Therefore, it can even be argued that the modern obsession with “things seen by the eye” actually distances us from truth, representing the lowest level of consciousness — one we share with animals, and often less sophisticated than theirs.

“You have to see it to believe it,” declares the famous maxim, containing an unexamined assumption about the eye-reality connection deeply embedded in many of us since childhood.

Is Color False?

One proof that things seen by the eye do not constitute absolute truth lies in how every living creature — including different sexes of the same species — perceives color in different ways and intensities. If what we see were absolute truth, how could different beings perceive it differently?

Research confirms that women perceive more shades of red than men, dogs possess less extensive color detail in their vision, and hawks demonstrate remarkable sensitivity to ultraviolet hues entirely invisible to humans.

In optical science, researchers acknowledge the significant bias each observer brings when examining colored data through a microscope. Scientific practice therefore commonly employs monochromatic “black and white” cameras, eliminating the unscientific bias of color perception to focus solely on gradations of gray. This facilitates the study of light rays, living cells, and materials.

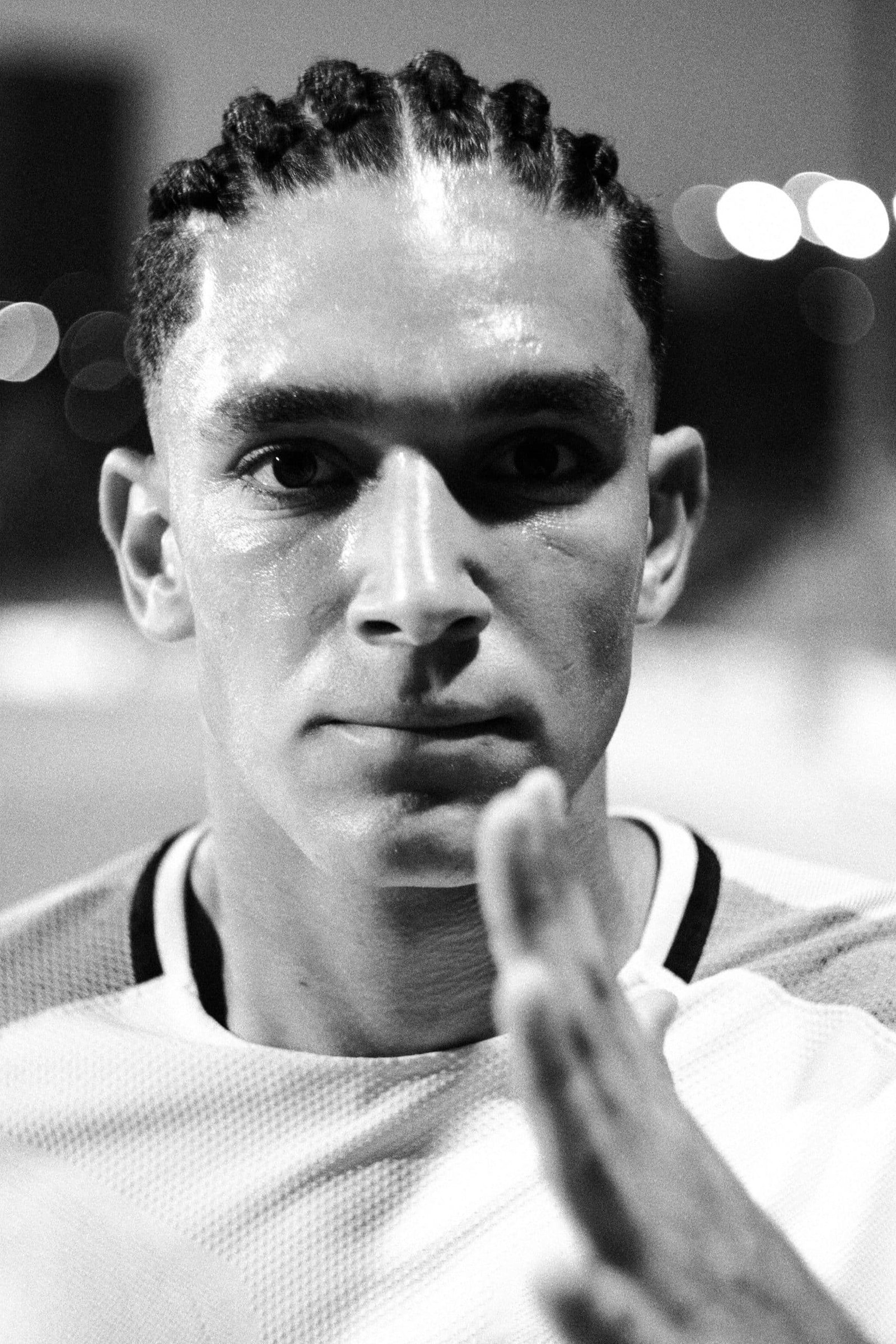

In photography, professional fashion photographers sometimes shoot and edit in black and white to better understand the relationship between lighting and subject — identifying where light falls too heavily or too sparingly. This proves extremely difficult to examine in full color because the human eye cannot distinguish between a naturally bright color and one that is simply better illuminated than another.

This is not to suggest that color represents a negative evolutionary mechanism; rather, it demonstrates that human vision alone does not constitute absolute truth. What we perceive with our eyes should not serve as the primary focus when learning new facts.

Consider synesthesia, a neurological condition involving direct neural connections between color processing and taste processing in the brain. Individuals with this condition may “taste” certain colors, though it defies conventional logic. So who possesses the limitation — the person who perceives only color, or the one who experiences color and taste simultaneously? One could argue that the “healthy” person is actually impoverished compared to someone who perceives color in layers of taste, if we indulge the prevalent assumption that everything visible to the eye must be absolute truth.

From Potential to Action

The relentless pursuit of “observable phenomena” that dominates the modern scientific mind, the soul of the news addict, the media consumer, and the diligent athlete seeking to master skill development — this pursuit cannot address the root of the problem nor cultivate intuitive judgment of good and evil, truth and falsehood, or performance-oriented psychomotor skills that emerge spontaneously.

Just as we would not repair a damp ceiling merely by repainting it (addressing the action) but rather seal the hole beneath the external tiles (addressing the potential), we should not approach athletic problems through atomistic thinking about which muscle supposedly serves a given action and which exercise supposedly strengthens it.

Instead, we must first address what remains hidden from the eye: inspiration, imagination, emulation of the finest among us, understanding causality, and multisensory anticipation of emerging abilities. Creating the proper foundation for spontaneous, artistic performances that express the internal soul rolling with minimal friction — only then do we arrive at action. And though that action employs those “false” components like subjective vision, it will ring true; for now those components are armored against irrelevance, inherent falsehood, and the processing difficulties that characterize the “seeing is believing” approach.

Consider parents who desire happiness and prosperity for their beloved fifteen-year-old son, so they decree: “You must study medicine and learn stock market investments, because statistics demonstrate that medicine provides stable income and stock investments are common among the wealthy — this path leads to happiness.”

On the surface, the parents are scientifically and statistically correct. Yet why do we feel a pang in our hearts at this declaration? Are we denying science?

Statistical decisions must emerge from a deeper internal world to gain the fuel to burn. In other words, we should not attempt to ignite the educational fire from scratch ourselves; rather, we must search for an existing ember and blow upon it.

Finding the ember serves as an inspirational point existing within the soul, leading to a path of least resistance up the ladder of action — particularly desirable when developing spontaneous abilities like creative thinking or athletic performance.

Athletic Atheism

After this foundation, we can characterize athletic atheism as follows: “Any physical activity that emphasizes instruction over the spirit of things,” or “any technical activity that emphasizes what is seen while ignoring what is hidden from view.” The term atheism here highlights the philosophy of “not believing without pictures,” common among those who seek to learn reality as it is, without theories.

This manifests both mentally-spiritually and physically.

Physically, the natural emphasis on “visible” mechanics alone manifests as neglect of what occurs behind the body and in the supporting structures: the posterior muscle chain, the movement of the back arm, or any required focus on ball or heel. The athletic atheist focuses only on what they see — toes, knees, front arm, head bent forward. Their body proclaims, “What I don’t see doesn’t exist,” and thus the untrained athlete appears hunched forward, perpetually curled into their fetal position from the womb.

Spiritually, the athletic atheist seeks the immediate, precise formula for their desired goal, rejecting long-term, deep-soul solutions that lead to genuinely creative spontaneous performances rather than repeating rehearsed “homework” during competition.

The “Obvious” as the Enemy of Performance

One reason the Red Fox system maintains such flexibility is that it does not take a collection of speed studies and apply them as a template for athletes. Examining various 100-meter Olympic finalists reveals different techniques, different stride lengths, different frequencies; some train heavily in the gym, others do not. Some are tall, some short. Some employ long ground contact times with high power output; others utilize quick contacts. Some collapse inward toward the arch of the foot; some do not. All are talented — and all reached the 100-meter world final, so they cannot be arrogantly dismissed as “wrong.”

Biomechanics and kinesiology truthfully demonstrate that efficient and inefficient levers exist; but the fact that a lever proves efficient does not mandate its use. Just as thinner car tires save fuel yet do not compel manufacturers to install only thin tires on sports cars — biomechanical truth is not necessarily the truth that should be applied in this place, at this time.

A constant dance exists between dry physical information and its field application for that specific “vehicle” which must perform spontaneously under unpredictable conditions while remaining reliable, resilient, and adaptable, both physically and cognitively. Therefore, the fact that a certain exercise or biomechanical principle has been researched as effective represents just one card in the hand called spontaneous athletic performance.

Spontaneous Performance

The ultimate goal when installing instructions, techniques, and insights into the athlete’s body and heart is to create spontaneous performances that originate from within and flow outward — not from subservience of the trainee’s body to the coach’s mechanics.

When an athletic action occurs spontaneously, the inner nature of that person flashes and acts as actual energy operating in the world through athletic expression — not from force of will but from deep motor readiness that has long departed the processing regions of the brain. Just as a flower opens its petals toward the sun in elegance, performing a perfect synthesis with the world around it, responding gracefully without calculating how and why, because correct mechanics are already ingrained. All that remains is to “arrive at the game and be who you always wanted to be” — to influence those you always wanted to influence.

Thus, the entire training process becomes an opportunity to scan various biomechanical and physical factors (hence the importance of knowing them) in the context of synthesis and the path of least resistance. Note that an opposite approach — where the athlete has learned nothing new — also creates resistance, since the clock will still show a slow run. The royal road lies in how to improve with the least mental resistance to what is being learned; here is where the art of coaching is measured.