The training process at Red Fox, because much of it is done implicitly and indirectly, generates many good questions that the curious athlete will ask in order to try to position themselves on the timeline and distance of the training program and arrive at a certain peace of mind.

In this new and foxy section, we will attempt to take common questions that arise among Fox trainees during the training program and address them briefly.

Sometimes the answer immediately satisfies the mind, and sometimes the answer requires continued “faith” from the questioning fox — something not easy, the ability to accept which we test in the admission screenings of new foxes.

Why is it necessary to learn to jump with both one leg and two legs?

As part of the process of acquiring athletic skills at Red Fox, we learn the mechanics of leaping with two legs (as in a box jump in the gym) in addition to leaping with one leg after momentum (as in a dunk from a step and a half in basketball). A two-leg jump may improve the jumper’s chance of timing the ball correctly because most of the power is produced vertically, which allows one to take the correct position while still on the ground and then simply launch upward. A two-leg jump for this reason allows taking a more aggressive position on the ground and surprising the opponent when required.

Indeed, a two-leg jump extracts a significant payment for the above advantage, and that is in the form of ground contact time. A two-leg jump has a significantly longer preparation time, a deeper dive of the center of gravity, and a greater demand for using the upper body as assistance compared to a one-leg jump. Because this requires extensive technical training, the ability to jump with two legs has been reserved only for those trained externally on the field.

Without doubt, a player who possesses the intuitive and technical ability to prepare vertical leaps with two legs and with one leg holds an aerial advantage over a player who relies on only one type of jump. According to all opinions, the soccer of 2030 is going to demand more and more from players, as we have seen in the last five years with the entry of young future stars into the professional leagues.

When to use each type of jump is a question that should not be learned through the intellect but through intuition. Yet from an external observation, one can see that an athlete chooses which form of leap to use according to these factors:

- The amount of time available to the athlete — the more time there is to organize for the leap itself and to anticipate the move, the greater the tendency to use two legs in the leap.

- The amount of space available to the athlete — the less space there is for the momentum required by one-leg leaps, the greater the athlete’s tendency to use a vertical launch with two legs.

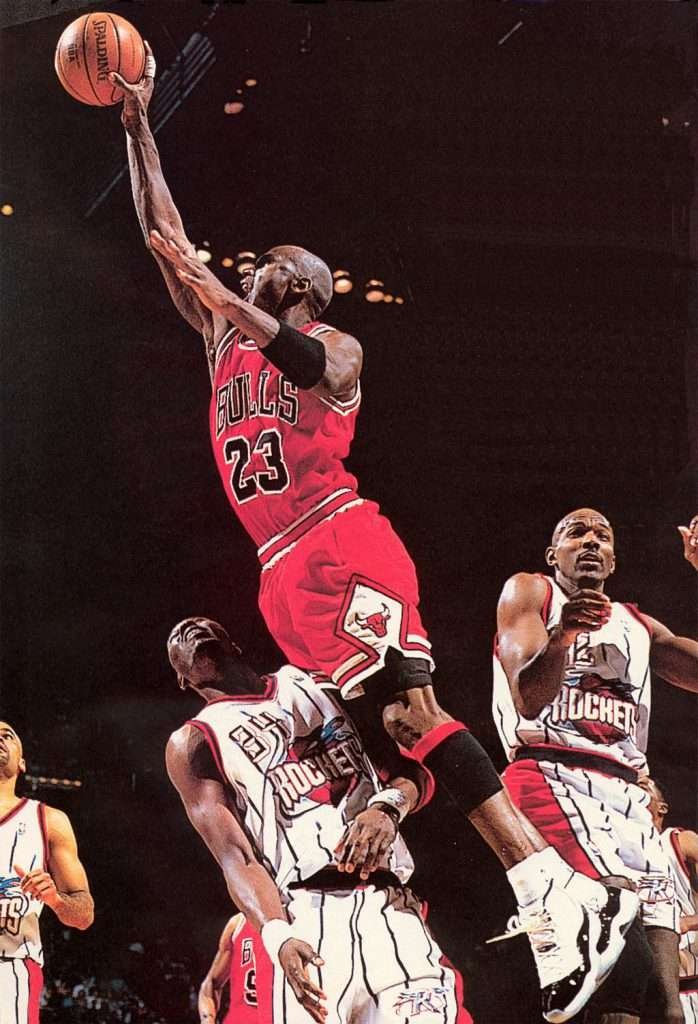

- The physical ability of the athlete — a one-leg leap naturally favors lighter athletes, with more tendon talent than muscle talent, which usually requires more time to express. In brief, tendon talent is the ability of the involved tendons to store and release energy efficiently and quickly with particularly low ground contact times. A two-leg leap favors a stronger athlete; for the sake of exaggeration, we can demonstrate that heavyweights arriving at CrossFit training will always intuitively jump with two legs, although long live the small difference between a heavyweight seeking to lose weight and Michael Jordan’s two-leg jump.

- The technical ability of the athlete — most of the population will tend more toward one-leg leaps because this type of leap uses momentum forces to compensate for deficiencies in power production (the engine) that will usually be found more abundantly among the trained. This does not mean that one type is better than the other; but if an athlete has already decided to train their body externally to sport in order to create tactical advantages over their competitors, all relevant subjects must be learned.

Average Ground Contact Times for Illustration

Single-foot contact at maximum speed in a sprint: 0.1 seconds per contact

Two-foot contact in landing and leaping from a box jump: 0.4 seconds per contact

Single-foot contact in a high jump: 0.18 seconds per contact

As can be seen, single-leg contacts buy ground reaction speed and the ability to enter a move later; in return, they pay with relative inaccuracy compared to two legs, lower power production, and a requirement for clear space for momentum.

Two-leg jump contacts buy spatial minimalism, significantly higher power production metrics, and great accuracy — and pay with longer engagement with the surface and a higher technical requirement.

Challenge both during training — it is perfectly fine to decide who you are and what type of jumper you want to be 80-90 percent of the time, but in sport, sometimes the situation will dictate for you what kind of jumper to be, and you had better be ready. Why do half the work if we are already dealing in athletics?

Michael systematically leaped with both one leg and two legs to maximize his advantage over opponents in every type of move

“But most of the game involves single-leg jumps”

Until when will we hide behind the specificity principle in capability development to save ourselves work? Never forget that if the specificity principle were universal truth, then the best training for capability development would be the sport itself without any addition. Since this is not the case, the specificity principle must undergo conceptual refinement in coaching universities — something far from being executed due to incessant emphasis on isolated motor skills (religious atomism by all accounts) in research laboratories.

Just as connecting gray cells together does not create human consciousness, so connecting mini-truths about which exercise contracts which muscle does not create an athletic dance.

I’m fast enough; can I work only on endurance now?

No, young fox. Training is not real estate in a registry. An ability that is not trained will lose its value very quickly; some faster than others.

A good program must include changing emphases according to personal and competitive need throughout the year, while preserving the old as much as possible.

There is no obstacle to installing your new speed within an endurance regime, but you need to think about a way to preserve that speed, even if only in technical form, whether at the beginning of sessions at low volume or on a day dedicated to speed at the correct loads.

Because the physical aspect will always be secondary in ball sports, there will always be compromises that will annoy the fitness coach; but this does not mean that one cannot be creative in solutions for preserving capabilities.

What is the difference between a plyometric session or conversions in the gym and athletics training?

This is a subject connected to the reservations described in the question about leaping. The question in other words is: what is the difference between stationary plyometric training in the form of small leaps on lines, jumps and landings from a box, quick contacts against a band, etc., versus athletics training that involves more complex mechanics.

If we compare this to the world of muscle, we can ask what the difference is between a fast squat with resistance bands versus a fast leg press machine.

PLYOMETRICS

The word “plyometric” originates from Greek and means “more” (plio) “length” (metric), and its use in the fitness field is usually to describe any activity centered on the effect of sudden stretch in muscle and tendon. This reflex actually bypasses the central nervous system when producing fast reactive force for a limited time. Many mistakenly think this is some fitness mechanism installed in the human body; but in truth, this is an evolutionary mechanism that provides a reflexive response, bypassing the nervous system (brain) for protection from predators or accidents/sudden dangers that require brainless intervention for survival (remind you of any game?).

It is customary to note that on average this response is most dominant at contact times below 0.4 seconds, but continues to operate in parallel to the nervous system up to 3 seconds from the initial stretch, at an intensity dependent on the speed of the initial stretch.

As such, plyometric contacts with the floor have become common among trainees in the form of “conversion” — which is the poet’s intention to convert the neural, conscious, and non-reflexive force gained from heavy weight exercises in which muscle and tendon stretch velocities are lower.

The science on the subject is clear: smart training of plyometric contacts that takes into account the great difficulty of managing their load in a training program will lead to improvement in stretch and subsequent contraction velocities, and in a manner specific to the movement pattern that was trained, for better or worse.

Yuval Ashkenazi

If so, one could also say that athletics training mostly includes plyometric contacts as well, so are you actually saying there is no difference?

Hush, young one.

The difference is in the approach. Yes, athletics training must include plyometrics within it to be considered athletic; but while plyometrics speaks of a purely reflexive physical phenomenon, athletics training speaks of a psychological-motor or “psychomotor” phenomenon.

Let us return to the difference between the fast squat with resistance bands versus fast leg press. Both exercises are plyometric and aimed at the stretch/contraction mechanism; but without doubt, the squat requires higher muscular coordination and technical skill in order to bring the stretch reflex to optimal expression.

From here comes the art component in training. The difference, then, is that in athletics training we gain conscious (not reflexive) coordinative motor skill rooted in a learning process that is mostly psychological — something that afterward, when we come to be specific with plyometric movements or simpler “conversions,” will be the difference between an athlete with superior results and an athlete who simply “trains” to squeeze out another half percent from average performances.

It is important to note, however, that sometimes we see athletes performing very complex plyometric movements such as Olympic lifts, two-leg leaps from momentum onto a box, etc. Therefore, one should not infer that the difference is only in the complexity of the exercise, but in the approach to the training process.

In summary, it is very important to train this discussed mechanism as part of the strength program; but it would be even better to install a more comprehensive foundation that can refine the plyometric contacts to be part of superior biomechanics, and in an automatic subconscious form.

If you have questions you would like addressed in the next installment of “Foxes Ask,” you are welcome to send them to the Fox email at the top of this website.