The joints of the body present a fascinating paradox: on one hand, they are axes of movement allowing mobility through space; on the other, they are vulnerable to injury precisely because of their complexity. In other words, their weakness lies in their strength.

The body’s joints are like having two doors instead of one in a house; there is the convenience of entering from an additional direction, yet also the risk of another door that can potentially be breached.

The body’s joints are also like remote internet access to an information system; there is the convenience of remote control, yet also the risk that an intruder may seize control from afar as well.

Before we begin discussing joints, we must understand that wherever there is mobility, there is complexity and risk of injury. Likewise, wherever there is an absence of mobility where it should exist, there is also injury risk. The premise of this article is that no universal law states that mobility equals injury prevention, as is commonly believed. When designing annual training programs, we must view the joints from several angles, in descending order of importance:

- As force-transfer surfaces that should remain within their “manufacturer’s specifications” as long as they stay in proper biomechanical patterns.

- As subjects of muscular activation patterns that surround and protect them; for example, the force ratios between hip flexors and glute muscles and their effect on point number 1.

- As subjects of non-muscular tissues (fascia, capsules, scar tissue, etc.) that influence point number 2, which itself influences point number 1.

- As psycho-motor expression in space; for example, the natural desire to dance to music we find meaningful or synchronized with the moment. The joints will move not only according to points 1 through 3 but also as part of a psychological-motor process connected to cognitive learning elements such as imitation, assimilation, and accommodation, which we will discuss later.

We will begin by briefly elaborating on each point above, with particular emphasis on point number 4, which has the most significant implications outside the physical therapist’s clinic walls.

I will note, of course, that joint health matters are the domain of the sports physical therapist; therefore, my writing angle will focus on athletic training itself rather than medical science.

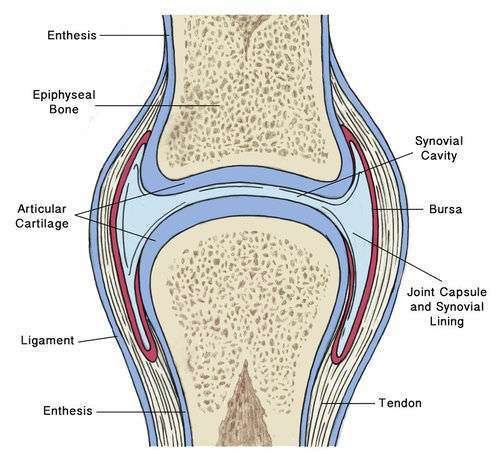

What Is a Synovial Joint?

Synovial joints are one of three types of joints in the human body. They are the most common and constitute nearly “everything that gets injured” statistically among athletes throughout their careers.

The synovial joint is a mobile connection point between two adjacent bones, characterized primarily by a joint cavity between those two bones, bounded by joint capsule tissue that also attaches to the bones.

Inside the joint, the force-transfer surfaces are covered with cartilage that functions like the coating on the Teflon pan in your kitchen, contributing to smooth movement between the two bones as they slide against each other within the joint.

Without this cartilage coating on the joint’s force-transfer surfaces, “grinding” of bone against bone would occur. Beyond excessive resistance to movement, this would impair the joint’s range of motion and activate pain mechanisms in an attempt to make you stop moving and preserve the joint’s continued function (osteoarthritis, or OA).

Atop the tissue bounding the joint cavity sits the synovial membrane, whose function is to secrete a special fluid with exceptional load-bearing qualities called synovial fluid.

This fluid is thick and resilient, functioning roughly like engine oil in a car. Its purpose is to further lubricate the articulation (coordinated movement) between the connecting surfaces forming the joint, as well as to provide nutrition to the cartilage itself, which contains no blood vessels and relies on metabolism (material exchange) with the synovial fluid and the bone beneath it.

This entire assembly is further covered by ligaments (some inside the capsule, some outside) providing additional support; together with tendons and muscles that securely close the entire structure. Between these additional support structures, further friction is prevented by fluid sacs called “bursae” that help separate areas where different tissues overlap, such as where a ligament meets a muscle.

The Joint as a Force-Transfer Surface

The very existence of these connection points; specifically synovial joints with all their complexity; indicates the accompanying existence of “manufacturer’s specifications” for each joint, describing the maximum forces that can act on the joint, the limits of motion, and, most importantly, the optimal force-transfer lines (vectors). In other words: the angles of each bone at the connection point during force production or absorption.

The most common form of ongoing joint damage found in most untrained athletes is producing athletic force atop a biomechanically weak joint position.

Let us review common mistakes athletes make when producing force during athletic activity; mistakes that gradually wear down joint surfaces and cause injuries in both the short and long term, in addition to obviously degraded performance. (Health and performance typically go hand in hand, fortunately.)

Toe joints (two in each toe times five toes): The untrained athlete will produce or absorb force against the ground via direct torque against the PIP and MCP joints of the toes, instead of producing it closer to the center of gravity (depending on the rest of the body’s position) around the midfoot/ball region, using the PIP/MCP only as energy transmitters rather than torque generators.

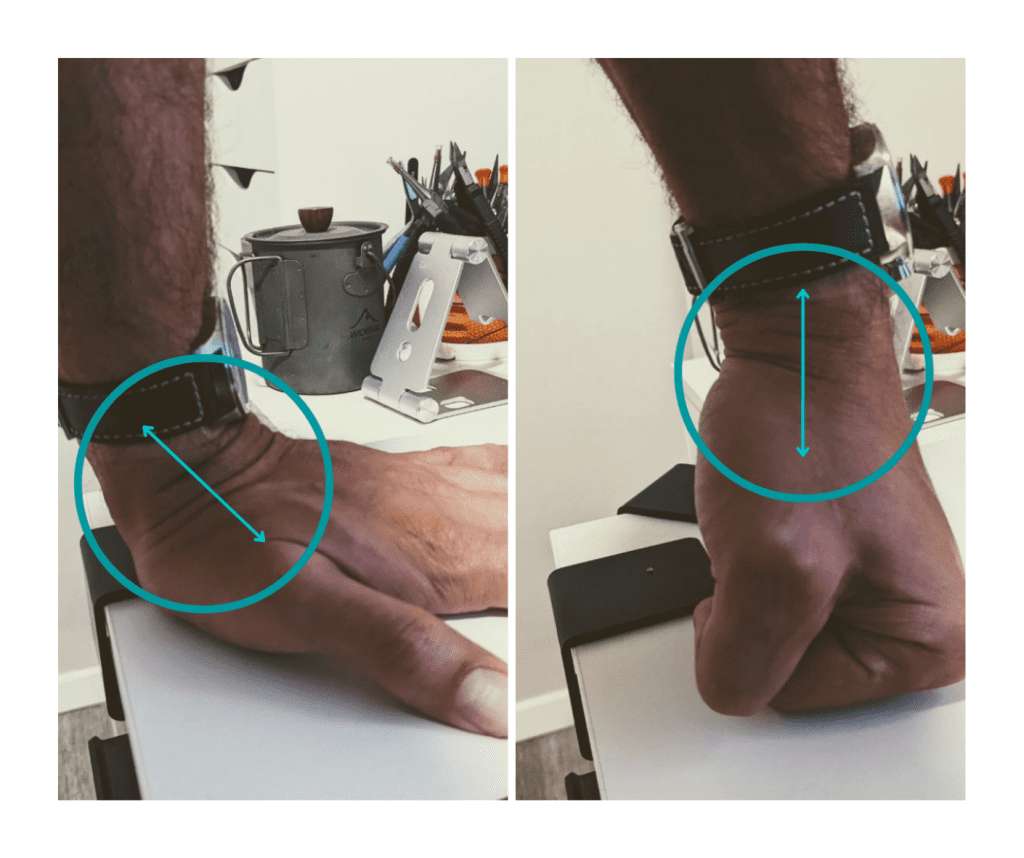

The ankle joint: The untrained athlete, consistent with the toe joints, will apply direct torque on the ankle joint against the ground while in a plantar-flexion (pointed) position. Depending on leg length and the plyometric-reactive action being performed, unnecessary force will act on the joint structure itself. Instead of flowing in alignment with the force lines generated by the large muscles of the legs and core, forces will “break” at the ankle joint and disperse at an angle that not only causes long-term wear but also reduces total force output.

The knee joint: A very forgiving joint on its face, owing to its limitation to a single axis of movement (flexion or extension). The limitation to one motion on one hand stabilizes it, yet on the other “exports” responsibility for it up the kinetic chain; specifically to the hip joints, pelvic position, and spine.

One can describe the knee as a captive joint; the quality of its function is dictated by movement quality at the ankle, hip, back, and pelvis. This transforms this stable, forgiving joint into one of the most injured among professional athletes who lack athletic education.

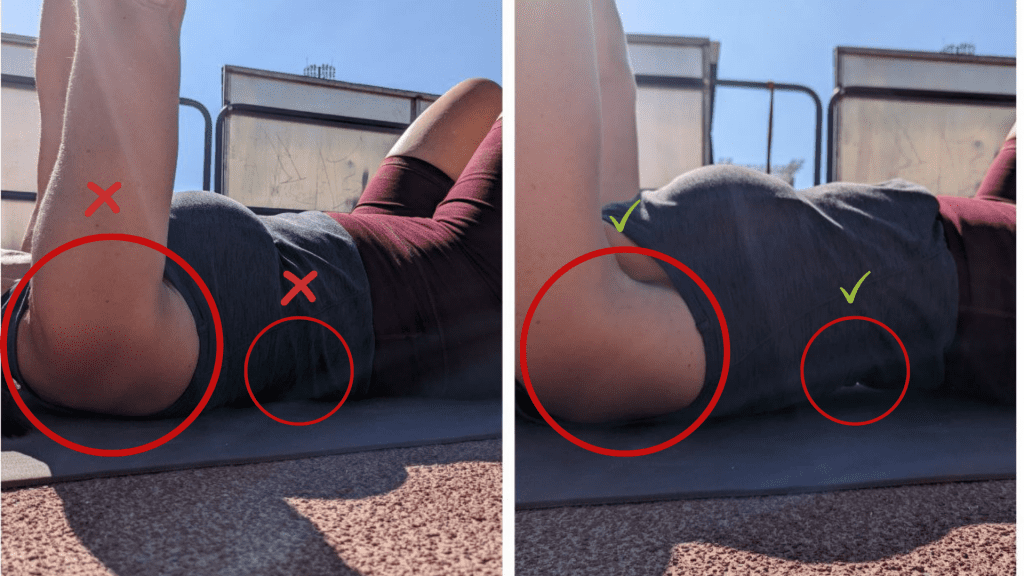

For example, during a bilateral jump, the untrained athlete will apply excessive torque on the knee joint if, during the loading phase, the hip flexors do not release enough to allow the hip and pelvis to enter the most compact forward rotation possible.

This desired state will result in more of the absorbed or produced energy being supported by the hamstring and glute muscles stretched as a result (muscles designed for sudden athletic actions), rather than excessive tension on the quadriceps, which should play a supportive role rather than assume full responsibility for force production.

The hip joint: A multi-directional ball-and-socket joint designed to allow three-dimensional movement. This joint functions as the main steering mechanism of the human body and is responsible for most steering actions; in the athletic context, often sudden ones.

The untrained athlete may do several things at this joint that lead to increased wear. First, similar to the knee joint, during a sudden direction change they will apply torque against the hip while the femoral head is in internal rotation combined with posterior pelvic tilt and a high center of gravity. This negates a considerable portion of the joint’s active support structure and leaves it exposed to handle the forces on its own. Initially, the surrounding muscles will respond with inflammation; over the years, the articular cartilage will wear and the internal joint structure will change accordingly.

The thoracic spine: This section of the spine contains 12 vertebrae and allows a very high level of mobility due to its connection to the ribs, unlike the lower back, which prioritizes core stability over movement, or the cervical vertebrae, which though naturally prioritizing movement do not need to handle very high torque.

This region plays a critical role in athletic activity requiring a low center of gravity, because one of the only ways to achieve a low center of gravity during athletic activity without “folding” is to rotate the pelvis forward, together with extension of the thoracic spine and slight knee bend.

The untrained athlete, for example, will perform direction changes while very “tall”; with a combination of vertical back and neutral pelvis, which applies unnecessary braking forces on the lower back instead of being dispersed outward from the body in a horizontal plane.

The shoulder joint: Another multi-directional joint designed to allow three-dimensional movement at the expense of stability. Due to its small size and the relative weakness of its supporting structures, the manufacturer’s specifications for this joint are also extensive.

The untrained athlete will typically treat all force production from the chest and shoulder as independent of it and will neurally release the supporting structures of the scapulae, trapezius, and small muscles stabilizing the joint during rotation. Specifically, this may manifest as excessive torque applied to the shoulder joint at weak angles, commonly seen during jumping, running, or various chest presses in the weight room.

The athlete will perform a bench press with the desire to “squeeze the chest” instead of pulling the scapulae back and allowing the supporting structures to do their work during the press.

Similarly, the athlete will perform athletic actions with scapular protraction combined with downward rotation, placing the joint structure in a biomechanically very weak position. This begins with inflammation and ends with tears in supporting structures and joint cartilage.

The cervical vertebrae: A region of the spine designed for maximum multi-directional mobility of the neck and head. As we have seen, wherever there is an option for maximum mobility, there is a demand for motor education due to elevated injury risk.

The untrained or motorically uneducated athlete will perform athletic actions with excessive flexion or extension, measured in continuity with the rest of the spine. For instance, if an athlete runs with a “straight” but angled back aimed at 45 degrees, yet at the top of the skeleton their neck is flexed down to 80 degrees (like smartphone users on a bus), there is a mismatch and terrible dispersion of forces traveling up the skeleton during athletic activity. Instead of gliding through the top of the head and passing from the body into the space ahead, forces will partially break at the exaggerated neck angle and again apply excessive torque on those vertebrae, along with significantly degraded performance.

There are many more classic examples for each joint, and we have reviewed only common mistakes. Yet already we can see how viewing the body’s joints through the terminology of “force-transfer surfaces” is effective for the long term, for the simple reason that such terminology hints at the joint’s performance nature; a new way of thinking about a body component traditionally viewed only through a rehabilitative physical-therapy lens.

The Joint as Captive of Muscular Activation Patterns

As noted, the joints do “know what they want”; yet ultimately, external factors such as neural muscle activation patterns, muscle performance levels under various load types (plyometric shock, maximal strength, low and prolonged intensity, etc.), and genetic limitations are what dictate joint movement.

We saw several examples in the previous section of how certain contractions and adjustments can place the joint in a position of mechanical advantage; a worthy goal for any athlete seeking maximum performance and longevity of the joint’s service life.

From a neuromuscular perspective, if we take, for example, the combination of the calf muscles with their opposing muscles; the tibialis anterior in front and the peroneals on the sides; we can see that a neural pattern prioritizing the calves at an imaginary ratio of 2:1 during athletic ground contacts will lead not only to significantly degraded performance but also to inflammation and stress fractures due to unbalanced forces acting on the tissues and bone during movement. Unlike the pure joint aspect of the ankle, activation concerns the forces acting on both sides of the bones during that ground contact. In other words, you can “err” in joint position yet remain protected because the supporting tissues; in this case muscles; contain the error. Thus excessive activation of the calf muscles and neural dormancy of the anterior shin muscles will eventually lead to injury and degraded capabilities.

Another classic example of faulty activation patterns in untrained athletes that causes degraded performance, back and knee pain, and hip-flexor inflammation is their inability to strike the ground while maintaining isometric hip extension. This usually occurs because the hip flexors are very short and “eager” to contract too quickly, combined with weak or dormant glute muscles; leading to an inability to strike the ground while maintaining a neutral pelvis with a tendency toward slight anterior tilt. This completely changes the forces acting on the hip joint, knee, and spine.

The two points above show that proper movement education is the key, absent genetic problems related to the joint.

The question arises: how did our ancestors before the scientific revolution know how to move correctly? Did the “Manufacturer” or “evolution” fail and create human beings who do not know how to move? Are we so arrogant as to believe that only through scientific knowledge of anatomy and biomechanics can we improve movement quality and joint health?

Let us switch gears for a moment and discuss how an athlete should grow in acceptable movement quality that enables health and performance without earning a doctorate in biomechanics.

Motor learning processes originate in the psychological processes related to a child’s cognitive and motor learning. If we discuss theories on “how children learn” in general, we can then hint at how this might be trained later in life as well.

The reason we focus primarily on children ages 4 to 12 is that they lack a developed intellectual mechanism that could explain learning processes. Instead, they rely on more primitive mechanisms that come as-is in healthy human beings and may hint to the future coach how to approach the question of improving motor patterns in athletes; not through a “college instructor” lens but through non-intellectual mechanisms.

The Joint as Psycho-Motor Expression of Movement

We have seen in the sections above that the human joint, in the athletic context, is essentially captive of the structures supporting it. The joint is a slave to the forces acting on the skeleton during movement.

The question then arises: can you simply read or hear verbal coaching (glutes back, head up, etc.) on how to perform a certain movement in the best way, and be satisfied with that in the annual training process?

The answer is both yes and no. Yes, because you will indeed execute the coaching you receive. No, because this movement will be at such low resolution and stuck in the “intellect” layer of human understanding that it will never attain the movement grace of an animal or elite athlete.

Did you notice, for instance, that the images were a critical part for you in the relatively complex explanation of proper joint angles? This is another hint toward the proper method of learning complex athletic movements, which involves stimuli from all the senses in addition to stimuli from multiple psychological dimensions and their integration in the movement context.

Jean Piaget was a Swiss psychologist who extensively researched developmental and cognitive psychology. A general review of his work may offer many hints for future discussion of athletic movement.

Piaget believed that cognitive learning in humans results from the following two processes:

Assimilation: Cognitive and behavioral coping with new situations through the existing set of abilities, behaviors, and memories (known as “schemas”).

Human beings will first approach what they know from past experience to cope with the new experience.

Accommodation: Accommodation forces existing schemas to change in response to a new experience, because the old schemas no longer adequately address the experience. Analogous to a “version upgrade” in the app world; something that keeps the app relevant amid ceaseless change in external factors.

The processes of assimilation and accommodation are always aimed at reaching “equilibrium” between external knowledge and the internal set of abilities. Because a person never reaches the desired equilibrium, assimilation and accommodation processes continue perpetually. (A connection point between Piaget and evolutionary mechanisms; the basis for evolutionary psychology.)

Let us begin with simple examples to understand the concept and then attempt to parallel learning processes to athletic movement.

When learning a new language, we use the language we already know to create a reference point through which we can understand the new language via translation (assimilation). After enough experience, we see that mental translation of the new language into the known one does not always work (for example, “orange” in English can mean both the color and the fruit), and therefore we must undergo “accommodation”; stop translating in that context and build understanding of the new language through new structures unrelated directly to our original language.

Another example is a toddler playing with bouncy rubber balls until given a cloth ball. The child tries to bounce the cloth ball unsuccessfully (assimilation) because in their understanding, anything round bounces. The child then learns through schema modification that not all round things bounce and that it also depends on texture. After several accommodations, one can also understand which materials bounce, how they feel in the hand, and so on.

In a motor context: an infant is born with the reflexive ability to suckle milk from its mother. The infant uses assimilation to suckle similarly from a formula bottle and reaches equilibrium (is satisfied). Later, the infant is given puree on a spoon or alternatively something soft by hand and tries to suckle it the same way. Upon failing to do so efficiently, the infant is forced to modify its feeding schema and add additional motor abilities of mashing and chewing, not just suckling (accommodation).

Now a training example: a beginner athlete has a certain conception of what it means to “run faster.” Usually, the beginner’s understanding of the speed concept is “higher step frequency”; the thought that through a faster step rate (like a mouse running) they will be more athletic. In other words, the athlete assimilates their knowledge of speed to approach the demand to run faster.

Subsequently, the athlete loses several times to other athletes for whom the concept of speed means “fuller and more urgent ranges of motion,” and through accommodation comes to understand that they need to change their schema or understanding of what speed is by one degree and aim for range of motion.

Of course, one can ascend many more resolution levels in failure and accommodation processes, especially in speed and agility training, because as we said, assimilations and accommodations are infinite processes. What happens, for instance, when all competitors understand that range of motion is the foundation of speed? Someone must still win, so accommodation in this case would be another step in elevating the resolution of what speed is.

Thus a very high number of accommodations will lead to an athlete who “has it.” When we see a great athlete, we are immediately struck by extraordinary inspiration at the simplicity of their movement. They are not thinking about things; they are simply present in the moment and executing, like breathing, like walking; with grace, athletic calm, and absolute effectiveness.

Much has been said about the young athlete needing to always be “in the moment,” but let us not forget that even the incredible elite athlete has gone through hundreds of accommodation processes stemming from small failures before reaching their expertise. In other words, there is a clear journey that must be taken to reach these levels, and it cannot simply be summarized in Buddhist spiritual quotes describing only the desired final state (if such exists) of mental and physical development.

One healthy approach to viewing the training process comes from the direction of music and dance. We never think about it, but the desire to move the body to music we find meaningful (something that happens even to those who do not know or even like to dance, surprisingly) is a thick hint toward using the skeleton and muscles as a mechanism of spiritual expression, for lack of a better term.

Without any dispute, people love music because it is an element that removes the burdensome logic of existential matters and replaces it with abstract patterns that call upon us to find meaning in them. Even this description is too logical for this wonderful and not fully understood thing. The fact that the nervous system, muscles, joints, and skeleton almost reflexively want to express that inspiration from music tells us that innocent, spontaneous movement can arrive only when there is a desire to express the athlete’s inner world.

This is the coach’s role: to honor and actualize the athlete’s unique inner world, to help them understand that their body has the ability to inspire others (fans, teammates, etc.), and to accompany the movement-learning process not only from a physiological-logical angle but also from a philosophical or spiritual one, for lack of a better term.

Sharp-tongued readers will immediately ask: “Then why doesn’t everyone who dances dance beautifully?” This is an excellent question. Why then is not every physical expression of inspiration through music beautiful to the eye? Why are there bad dancers if it is so innocent and spontaneous as we claim?

Every desire to express oneself to others, whether through speech, dance, music, or facial expressions, will require hundreds or thousands of assimilation and accommodation processes to reach high resolution. We must separate the natural “reflex” to express the inner world through muscles and joints; which is a sacred thing in itself; from the quality of that expression, which demands many rounds of failure and learning.

No matter how long and winding the road

I cannot stop walking, cannot quit

Leaving behind the fears and the sorrow

Everything is everything, I must continue

All that happens I know must happen

I am the fire you cannot extinguish

The music will take me up and deep

The long road; to walk it is to live.

The music will take me up and deep; the song “Falling and Rising”; Shabak S

Movement in the Context of All the Senses

For movement ultimately to become an expression of the inner world and inspire others; whether fans, teammates, or you yourselves; the learning process must involve as many “mechanisms” of sensing and consciousness as possible.

One way a trainee learns proper movement is through imitation of a player they admire, or through their coach’s demonstration, if the trainee is fortunate enough to have a coach still capable of performing at a level that inspires. Imitation is the most powerful technique a young athlete has in the learning context. I have personally witnessed athletes learning complex movements in very short time simply because of their great love for the athlete they were trying to imitate. One should always encourage the inspiration other athletes bring us, just as we want to become those athletes ourselves one day.

However, at Red Fox we try to cover multiple sensing mechanisms for every simple action. There are several questions we ask with every important drill, in order to assimilate the knowledge derived from it across numerous systems in the body and create learning at such a depth that it will remain tattooed as part of the body, even in the extreme case of absence from training or injury.

Sample questions during movement learning:

- What does it look like?

- What does it not look like?

- How does it feel? (Naturally there are many answers to such a question; I want all of them in minute detail.)

- What sound does it make? What does proper movement sound like?

- What is the difference between the sound of good movement and the sound of poor movement?

- What shape does it draw with the hand or leg?

- What does this movement remind you of?

- What do you want to say through this movement? What are you trying to broadcast?

Not all answers are necessarily related purely to the drill’s technique, and not all answers will be relevant to the training itself, but because dozens of physical and psychological mechanisms are involved in the answers while physically learning the drill itself, the learning will presumably carry such weight that it will remain tattooed as part of the body, even in the extreme case of absence from training or injury.

This approach, because it honors the athlete’s personality and places them at center stage, allows them to be themselves and express their dreams in every movement that would otherwise be “just movement.”

Once an athlete reaches a state where they express themselves in their movement, with such breathlike lightness and spontaneous confidence, we can all agree this is one of the most beautiful things to witness. There is a very, very good reason these people receive nearly unlimited money to display their talent on a weekly basis.

Be Quiet and Deliver

There is a certain feeling when reading a theoretical thesis based on personal experience like this article that there is more information than the brain needs to absorb.

I understand your heart and say you are entirely correct! The athlete’s role is not to know everything by heart and remember it for an exam, but only to understand between the lines; each person whatever they can take to be better at their craft tomorrow. This is the main purpose of the articles written here.

One can indeed say that if you did not take more than a line or two home after this article, that is perfectly fine; two lines is already more than zero!

At the end of the day, proper movement will feel natural and correct, and will be measured as faster and more efficient. So relax your face, release your shoulders, and surrender to learning through imitation, assimilation, and ceaseless accommodation. Leave the rest to the strength coach you trust, the physical therapist who cares for you, and the professional training staff that wants to bring out your best.

Summary

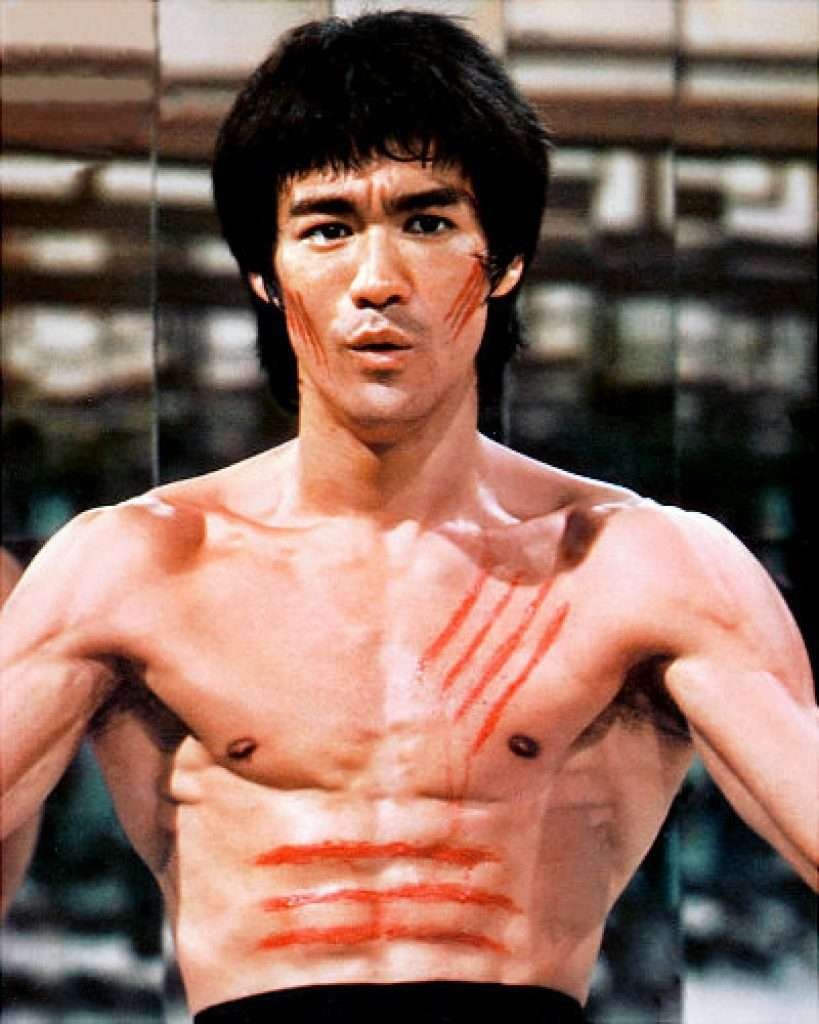

The entire article can be summarized in the following wonderful quote from Bruce Lee:

“Before I learned the art, a punch was just a punch, and a kick was just a kick.

After I learned the art, a punch was no longer just a punch, and a kick was no longer just a kick.

Now that I understand the art, a punch is just a punch, and a kick is just a kick.”

Bruce Lee

This description shows us the nature of repeated assimilation and accommodation processes. At first, things are very childlike and innocent, beginning very simply though not particularly effective in the real world. With the learning process, our eyes open to the infinite learning possibilities in our world, and with all the advantages therein, as King Solomon said, “He who increases knowledge increases sorrow.”

Finally, there comes a combination of the healthy, childlike, innocent mental state of the beginning, yet with the abilities developed after the learning process. Such a psycho-motor state is the desired state for an athlete, and one should strive to reach it in every single training session, in contrast to the classic instruction of “do X to muscle Y and you will automatically get Z.”

The athlete’s consciousness is a world unto itself that even in decades will not reach scientific exhaustion, and any attempt to remain overly “physiological” in the training process will harm the athlete’s proper development.

Each and every one of you holds a unique weapon that no one else in the world has or ever will have. Learn to wield this weapon in battle, for it would be very sad if you did not do so with skill and expression; after all, you are the only ones in the world with this weapon.