If you’re starting an intensive training session focused on speed/agility components with a rolling wheel exercise, light jogging around the field, a collection of floor exercises, and a stretching circuit — this is exactly the post for you.

Let’s try to understand the unique needs of speed/ball sport training, which types of warm-up serve them and which don’t, and we’ll see an example warm-up with explanations.

By the end of this article, you’ll be armed with a number of simple and quality tools that will upgrade your entire program.

The “Bullets” of the Athletic Gun

If we look at the elements of speed and agility as a gun, what are the bullet properties this gun should fire? If we can answer this question, we’ll know how to plan the beginning of the training session and thereby how to properly load the athletic gun, as the manufacturer intended.

Below are the most important athletic warm-up properties that have been interwoven throughout its connection to proper warm-up planning:

- Training is more nerve-intensive than endurance-intensive. In other words, more “violent and sudden” rather than “strong and patient”.

- Movements in body joints are defined as intimate dancing with stiffness paired with mobility (ankle, knee, hip, back, neck).

- The stretch/contraction process in the muscle itself — defined as plyometric (reactive) instead of isometric.

- The psycho-physiological arrival at a “speed state” — in animals and humans — defined as “pushed but released” — neither of these two properties can exist on its own.

Principle #1 — Training is More Nerve-Intensive

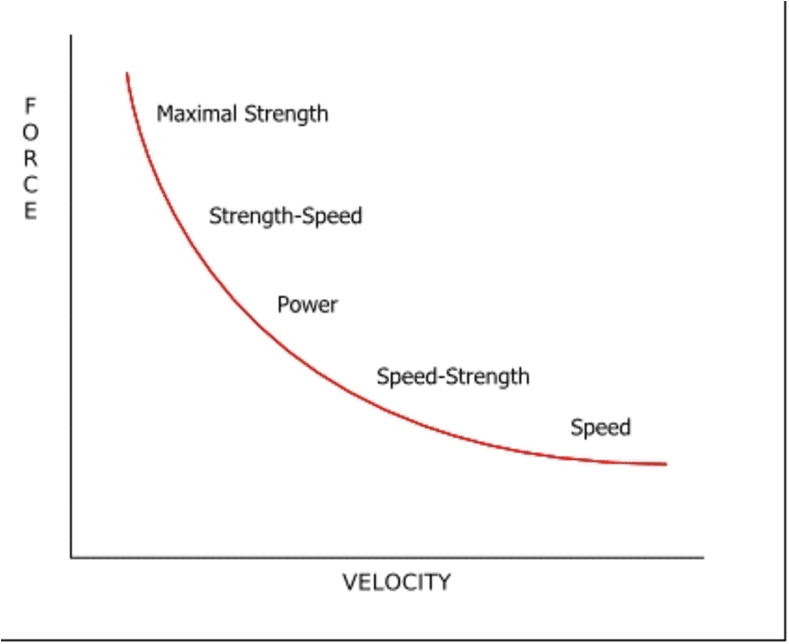

In the famous graph that describes what happens to force output when working at contraction compression levels (force drops significantly), one thing can be understood — it’s impossible to be both very fast and pushed, and also to be very strong and apply all the force we’ve built in the weight room.

In speed training, it turns out, the character will be shifted toward speed on the graph, and if drills or exits to the field are added that are too short, then we can also talk about speed-strength — while Power and above is already reserved for the world of weightlifting.

If so, this gives us a powerful hint for the character of a good warm-up, which besides the obvious element of raising body temperature, will need to give a proper response specifically to the force/speed curves we’re going to work on.

This assumption has several caveats: specifically, the often-critical effect of maximum force exercises (squats and such) before specific drills (known in the field as “potentiation”), but one shouldn’t get more excited than necessary about the temporary effect of a cheap nerve trick on a real long-range ability that can be relied upon.

The graph also doesn’t hint at additional common mistakes, and it’s warming up maximal endurance components (building muscle protein during the warm-up itself) before a pure athletic session — as is known, protein building is a slow relative process, and any excess accumulation during warm-up could impair the entire rest of the training.

Courtesy of www.researchgate.net

Principle #2 — Movement Character in Joints

Movement in joints during fast/agile athletic activity is one of the most fascinating things in the human body.

There’s a maximum combination of stiffness and mobility here, interwoven in an obsessive relationship where each one tries to dominate the other, but their forces are equal and therefore there’s no clear winner.

Let’s look at the major joints one by one and try to understand the key to action:

- The ankle joint — its path will pass force from the primary motors (the muscles) and its path will return the response from the ground — and just as so, it will need to be stiff outside the ground to allow maximum stride length (the toe raise method). It turns out the ankle joint will need to be stiff when touching and flexible in the air — an amazing combination.

- The knee joint is a fairly simple single-axis joint without much room for error, and its function during athletic movement is to remain in its simple axis during ground contact (stiffness) but flexible (due to buttock) in the air.

- The hip joint is a highly multi-directional ball joint whose main function is to provide thrust vector from the primary motors (the muscles) and therefore it will need to be both stiff when touching, and freed in angular thrust change. It needs specific mobility in the air as well, because as this joint moves away from its midpoint, the push potential decreases and the speed of that movement will be lower.

- The mid-back/thoracic spine is the most flexible area in the back, and is capable of performing significant flexion and extension, like a door of a saloon in movies. With an athlete touching the ground, given its flexibility and the poor force in most athletes, it will be challenged when calling for bending as a whip. A joint like this needs to also learn to be strong, but flexible in bending direction. This is similar to the neck vertebrae, less relevant for this post.

Principle #3 — The Stretch/Contraction Process in Muscles

The motor activity itself, during athletic movement, is proven to be reflexive and toxic. For example, during athletic ground contacts, the body will have about 0.2 seconds to apply maximum force, which doesn’t leave much room for organized force production like in a squat in the weight room — but rather emphasizes the need for fast stretching and release in contraction, exactly like a jumping slingshot, which was very much engaged before the iPhone was invented.

This gives us a powerful hint, that if we exaggerate with static stretching of the muscle during warm-up, we’ll disable a non-negligible part of that slingshot mechanism that’s woven into the motor units in the muscles, because we’re signaling to the body that we want more range than force, and the body will give us exactly that (and prepare us for non-athletic activity).

The primary motors again, like the joints, show fascinating relationships between release and contraction. They want to be released enough to allow the slingshot to stretch, and they want to contract enough to provide maximum possible force in such a short time.

Principle #4 — Psychological Preparation for Training

Beyond the physical components, there’s also a mental component to preparation for fast athletic training.

As written in the article “The Secret Power in the Nervous System” — the root of every quality athletic action is found in the nerve instruction from the brain, which is itself subject to psychological preparation that’s part of the training itself.

A warm-up that doesn’t provide psychological response to the upcoming athletic training will catch the player not mentally ready for the “battle” that is athletic training. It’s hard to imagine entering a real battle without any battle-like training in the form of fighting pressure, idea tremors, and such — or getting a football player ready for a game with theoretical knowledge alone, without actual training in maximum force tackles against other people.

On the other hand, a warm-up that allows the athlete to look inward as a goalkeeper before the exercises themselves, will create a psycho-physiological state that favors the long range with the desired approach to the whole athlete that can be relied upon to perform any day, and any hour. A small part of the famous name “Red Goalkeeper” is in the balance zone the coach creates between speed, cunning, agility and thought — and this is a philosophy we take also to athletic performance.

Clarification

The fact that weight training, endurance training, or any muscle protein building isn’t found on the graph above doesn’t mean it’s not effective. In this article we’re only talking about preparation for pure speed training, and we’ll leave the opinion on the biggest weakness of athletes in Israel — which is a mental slow state for any sport that includes speed and agility as its main component.

Maximum weight training has its own “warm-up” — because if the principles are similar — the mental approach to training is a bit more patient than athletic contractions. As mentioned above regarding endurance.

In any case, if we’ve determined that warm-up is the key-giver of that training, it’s likely there’s great importance, especially when looking at an annual training plan, in how we approach training sessions.

Example Athletic Warm-Up

If we wanted to train speed with sprint and agility components, we could take a scheme like this as a starting point and edit it to match the athlete:

Phase A — Raising Body Temperature — Preparing the Muscles Thermally.

- 1-2 minutes of running or jumping on rope

- Squats, lunges, half-lying pushups, slightly open

- Climbing stairs

- Any short but basic activity that will bring a slight increase in body temperature

Phase B — Joint Warm-Up.

- Ankle mobility toward wall.

- Dynamic stretching of the four heads, hamstrings, hip flexors, hip and back.

- Frontal and lateral leg swings.

- “Camel threading” for the back.

- Hip rotations in several forms.

- Wide/hip rotation positions for minimums.

- Shoulder rotations for minimums.

- Pulls.

Phase C — Preparing the Nervous System.

- Progressive runs to 30 meters.

- Isolated activation of buttock muscles (both types)

- Fast staircase speed drills to 5-10 seconds.

- Fast forward lunges.

- Backward run to 30 meters.

- Skips with one leg to 30 meters.

- Running jump exercises for minimum to 15 meters.

- Squat walks.

Phase D — Fast Combination of Phases A, B and C — For Psychological Readiness.

Here we raise the pace intensively (but still submaximal) — and perform combinations that involve mainly phases B and C — for example a pull exercise from phase D — will combine the flexibility from phase B but with the force of phase C for one exercise.

When we’ve warmed the muscle, moved the joints and muscles to their range, and then used them in a fast and flexible yet momentary way, and we haven’t waited for the agility exercise itself to speak about agility — then we can arrive at the main components with confidence.

Which Leg Did You Get Up On Today?

The famous question applies also to athletic training. The warm-up must serve the psycho-mechanical components not only in terms of that training’s performance — but also in terms of creating a reliable system with less “bad games” and less “I was tired in the game” throughout the career — the magic ability to imitate the partner’s goalkeeper, even under relative fatigue, changing moods, and external factors for sport. The warm-up is a mental ritual exactly as it’s a physical component, and through it one can reach stability and confidence in performance — the most valued athletic feature among coaches in sport.